While board self-assessment is recognised by organisations including ASX, DHHS and AICD as an accessible, flexible and sound contributor for understanding and improving a board’s performance, the issue of subjectivity within a self-assessment is a long-standing point of discussion and debate.

How realistic are boards at self-assessing their own performance?

While the issue of subjectivity within a self-assessment is a real consideration, there are methods a board can employ to reduce the influence of subjectivity from the outputs of a board self-assessment.

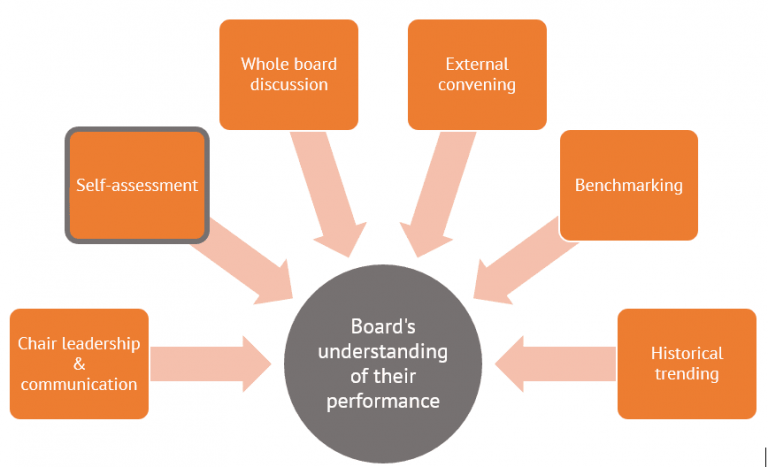

As illustrated below, the most important action a board can take to counter any subjectivity is to ensure the self-assessment is not the sole source of information, but rather is one of several key elements in the evaluation process.

These elements should include:

- A self-assessment questionnaire that asks about aspects of good governance that require supporting evidence rather than simply seeking perceptions. For example, a question may ask about the presence (or otherwise) of a policy or procedure, and the regularity of updates. This requires a more objective response than asking about how the respondent feels about the board’s performance in relation to the same policy or procedure.

- Leadership and communication from the chair so that the board are assured about the confidentiality of their responses and the subsequent ways in which their responses will be used. For example, for professional development.

- Ensuring a whole board discussion of the self-assessment findings takes place, which triangulates responses between members, and between group behaviours and responses.

- Periodically bringing an objective aspect to the evaluation by engaging an external independent convener to facilitate the group discussion, or to enrich the entire evaluation and capability building process by undertaking desktop reviews, director interviews, and by facilitating and building group and director action plans.

- Benchmarking the results of the board evaluation to those of other boards in similar industries and environments. Confidential benchmarking against the cohort average as well as the best performing boards in the cohort will stimulate further conversation about the board’s self-assessment findings.

- Historical trending of results, so that themes that may have emerged in initial evaluations can be tracked in subsequent years.

How do boards translate the results of the evaluation into improvements?

As well as the often-legislated requirement to ensure delivery of safe and quality services via a culture of continuous review & development, it is crucial for the morale and drive of the board members that the time they invest in undertaking a robust evaluation is rewarded via assurance that the evaluation will result in more effective governance of their organisation.

The first step to achieving this is for the evaluation process to be comprised of multiple elements (as described above).

Secondly, while the evaluation process is a vital snapshot in time, equally important are the discussions and actions that follow the evaluation. There are a variety of methods to translate the results of the evaluation to inform the group discussion:

- In an independent convener led process, the convener analyses the outputs of the self-assessments, confidential interviews, desktop review, peer review and committees review and presents them to the board as a recommendations report for review and discussion.

- In a chair led process, the chair analyses the outputs of the self-assessment and confidential interviews and presents them to their board either as a recommendations report or a facilitated discussion.

Thirdly, with the priority areas identified, the board action plan must be built to convert the priorities to actions and then ultimately to results. The board action plan must include SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely) actions set against each priority area that are assigned to a responsible person, and be tracked against deadlines. Regular review of the board action plan is vital to ensure that it remains current and actions are followed through across the remainder of the year.

Individual action plans must be built in concert with the board action plan, which are developed and used by members to resource and address any individual gaps in knowledge, experience or skills uncovered during the evaluation process. The importance of gathering and acting on this information is also recognised by ASIC in their most recent Governance Principles.

Next, the beginning of each new year provides an opportunity to challenge, and confirm or reset, the board’s current priorities by comparing performance to the average and best performers in their industry cohort via a board review of their Governance Capability Benchmark Report.

Finally, annual re-evaluation is a vital component of continuous improvement, as it highlights areas of development and new areas of focus for the next capability building cycle.

The very act of evaluating, discussing, choosing actions and being accountable for their implementation, then measuring both internally and externally, sets the culture of quality and continuous review and development from the top. As the Royal Commissions and prudential enquiries have determined, this type of culture is essential to effective governance and quality delivery of service.